|

||||

|

||||

Gene Dixon Memoir |

||||

|

||||

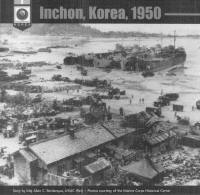

Inchon, Korea, 1950--the landing that couldn't be done |

||||

"The successful assault on Inchon could have been accomplished

|

||||

| Allan C Bevilacqua. Leatherneck. Quantico: Sep 2000.Vol. 83, Iss. 9; pg. 18, 7 pgs Copyright Marine Corps Association Sep 2000 |

||||

|

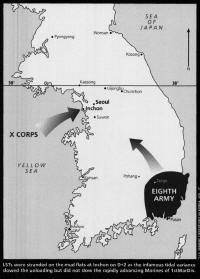

By mid-August of 1950 the American and allied troop situation in Korea was fast becoming critical. Under relentless attack by a North Korean People's Army (NKPA) that was superior in numbers and equipment, friendly forces had been driven to a small perimeter of resistance about the vital port city of Pusan on the southernmost tip of the Korean peninsula. Clinging grimly to this last bit of real estate, the defenders awaited the all-out offensive that was designed to drive them into the sea. The gravity of their position was vividly illustrated by the words of a British military observer who wrote of the very real possibility of "being faced with a withdrawal from Korea" if the coming onslaught was not turned back. It was in this atmosphere of crisis and danger, confronted with the specter of defeat, that one man was thinking in terms of victory. Faced with an enemy who had known nothing but success, with his own forces battered and barely holding their own, General Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of allied forces in Korea, saw the opportunity for a smashing counterstroke. Victorious though it may have been thus far, the NKPA, in MacArthur's estimation, had just about run out of steam. What the communists had gained had not been won without cost. Their frontline troops had been chewed up, their supplies were being eaten up fast, their vehicles were beginning to stagger and stumble for want of maintenance. If the weary troops holding the Pusan Perimeter could stand their ground just a little bit longer, the North Korean invaders would be ripe for a knockout blow. What MacArthur had in mind was not merely turning back the North Korean forces, but completely destroying them.

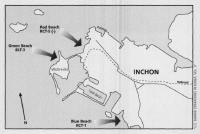

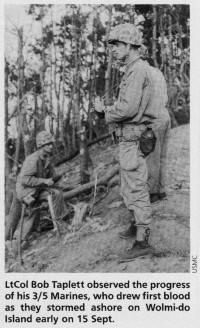

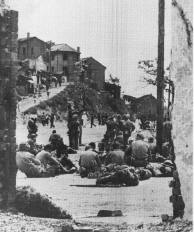

Like other invading armies before them, the North Koreans had driven into the South by way of the natural terrain corridor running through Seoul and on southward in the western region of South Korea. It was along this route that the long NKPA supply line ran. Sever that supply line, and the NKPA forces ringing the Pusan Perimeter would be cut off from their strategic base in the North. The attackers would become the defenders, faced with enemy forces in their front and rear. In MacArthur's judgment, there was only one place to cut the NKPA supply line, one place that would permit the total destruction of the NKPA. That place was the port city of Inchon on South Korea's west coast. An amphibious assault at Inchon and a swift drive inland would seal the fate of the NKPA. There were other possible objective areas, but none offered the potential for putting the NKPA's collective neck in a noose. Inchon was the strategic center of gravity for the entire situation in Korea in midsummer of 1950. Seize Inchon, and in the words of a long-forgotten Confederate soldier in another war, "You git to play th' music while th' other feller has to dance." The catch in the whole thing was that Inchon was a hydrographic nightmare, one fit to bring an amphibious task force commander out of a sound sleep with his heart pounding. The shallow waters off Korea's western shores were a natural barrier to deep draft vessels, affording access to the coast only by narrow, restricted channels. The approach to Inchon was particularly tricky, a twisting passage through a maze of sand bars and mud flats where an incautious skipper all too easily could run aground and block the passage of every ship that followed him. Strong water currents multiplied the chances for mishap. Beyond the harbor approach itself there was Inchon's infamous tidal range, among the highest in the world, where the difference between high tide and low tide could reach almost 35 feet. What might be a usable landing beach at high tide became a mile and more of untrafficable mud flats at low tide. If that weren't enough, the peak high tide necessary to meet the draft requirements for LSTs (tank landing ships), would last only three hours and would occur on only a few days in mid-September. Among these days the best of a bad lot was 15 Sept. Even then tidal conditions would not be good, merely the least bad. Lastly, there was Wolmi-do Island. Connected to the mainland by a causeway, Wolmi-do sat squarely between the boat lanes leading to the only practicable landing beaches. Before the problem of Inchon could be approached, Wolmi-do would have to be neutralized. As a practical matter then, the Inchon operation would have to be conducted in two acts. Wolmi-do would have to be secured before anything else could happen. Then the entire amphibious task force would be forced to sit twiddling its thumbs while it waited for the next high tide 12 hours later. Interesting things could happen in those 12 hours, things admirals and generals don't like to think about. Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, whose Task Force 90 would be faced with the problem of negotiating these daunting obstacles, was an old hand at amphibious operations. A veteran of many such undertakings in the Pacific, RADM Doyle was widely recognized as the Navy's premier amphibious commander. Considering the many complexities of a landing at Inchon, he had only this to say at a meeting with MacArthur on 23 Aug.: "General, I have not been asked nor have I volunteered my opinion about this landing. If I were asked, however, the best I can say is that Inchon is not impossible." If RADM Doyle was confronted by monumental problems getting the task force to the objective area, the commander of the landing force, Major General Oliver P. Smith, had the equally daunting task of putting that landing force together from scratch. MajGen Smith's First Marine Division was scattered to the four winds. One of his regiments, Lieutenant Colonel Ray Murray's 5th Marines, was at that very moment heavily engaged in combat in the perimeter ringing Pusan. The Ist Marines, led by the redoubtable Colonel Lewis B. "Chesty" Fuller, and hastily assembled from Marines plucked from posts and stations throughout the Marine Corps and recalled reservists, had not even reached Japan. Like the 1st Marines, Col Homer Litzenberg's 7th Marines had not even existed except on paper two months earlier. How bare the cupboard was could be seen by the fact that Litzenberg's 3d Battalion had only days before been the 3d Bn, 6th Marines. Afloat in the Mediterranean when fighting broke out in Korea, the battalion had been rushed through the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean, donning its new identity en route. The 7th Marines would not arrive in the area in time to take part in the landing. MajGen Smith would have to conduct a division-size assault with only two regiments that had never trained together. Nonetheless they would land, and they would land on 15 Sept. At 0520 that morning, after two days of constant pummeling by naval gunfire, the traditional signal, "Land the landing force" was raised to the truck of the mast of RADM Doyle's flagship, USS Mount McKinley (AGC-7). Even as the assault elements of LtCol Robert "Bob" Taplett's 3d Bn, 5th Marines boarded the landing craft that would take them to Wolmi-do, gull-winged Corsairs of Major Arnold Lund's Marine Fighter Squad- ron (VMF) 323 and Maj Bob Keller's VMF-214 continued to paste the island with bombs, rockets and napalm. Firing almost point-blank, the destroyers Southerland (DDR-743), Gurke (DD-783), Henderson (DD-785), Mansfield (DD-728), DeHaven (DD-727) and Swenson (DD729) pumped more than 1,700 5-inch shells into the cave-sheltered NKPA artillery defenses. From farther downstream the cruisers Rochester (CA-124) and Toledo (CA133), along with the British cruisers HMS Kenya and HMS Jamaica, added their 6- and 8-inch projectiles to the hailstorm. Completing the rain of destruction, the three rocket-firing LSMRs (medium landing ship, rocket) of Commander Clarence T. Doss' Fire Support Unit 4 saturated the defenders of Wolmi-do with 3,000 5-inch high explosive rockets. Watching from the bridge of Mount McKinley, Lieutenant General Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr., Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, whose battlefield experience stretched back to France in 1918, noted, "I have never seen any better shooting. The entire island was smothered with bursting shells from the cruisers and destroyers." It is entirely likely that the North Korean defenders of Wolmi-do-a hastily collected and barely trained hodgepodge of conscripts-failed to share LtGen Shepherd's view of the scene; they were completely stunned. The pulverizing barrage continued almost to the moment the ramps of the LCVPs (vehicle and personnel landing craft) of the assault waves dropped on the designated landing points. Private First Class Fred Davidson, a veteran of the August battles in the Pusan Perimeter, was a rifleman in Lieutenant Bob "Dewey" Bohn's G/3/5. "It got quiet as hell," Davidson recalled. "The only sounds were the LCVP's en- gine and the slap of the water on the bow." Then a flight of Corsairs roared in. "The roar of their engines hit us like a bomb. Those Corsairs came flying through the smoke toward the beach not more than thirty feet over our heads. Hot, empty shell casings fell on us. Talk about close air support!" the PFC said. Then Davidson and everyone else got too busy to notice the perfect timing and execution of the assault. With "How" and "George" companies abreast, the lead elements of 3/5 swept over the landing beaches and made for their initial objectives. Captain Pat Wildman, How Co's commanding officer, immediately sent two squads to secure the very northern tip of Wolmi-do, then drove the bulk of his company to the far side of the island to block the end of the cause- way leading to the mainland. Combat engineers attached to the company lost no time in placing an antitank minefield to prevent a counterattack from the city. That done, Wildman swung to his right, keeping up with Lt Bohn's George Co, which was even then seizing the island's dominant feature, a 350-foot height known as Radio Hill. Resistance was light, scattered and ineffective. Those North Koreans who chose to fight were quickly dispatched. Others were herded off dazed and incoherent with their hands above their heads. By 0650 LtCol Taplett had his reserve company, Capt Bob McMullen's Item Co, and a platoon of M26 tanks ashore. It was about then that the crew of an enemy armored car had the bad judgment to venture out of the city and onto the causeway. The long-barreled 90 mm gun of Staff Sergeant Cecil Fullerton's tank cracked once, and the armored car exploded. A handful of North Koreans, bypassed by the assault waves, tried to make a fight of it from the caves where they were holed up. Working their way methodically, tank-infantry teams sealed up each cave in turn, entombing the occupants. Shortly afterward Taplett was able to transmit the message, "Wolmi-do secured at 0800." The seizure of Wolmi-do had gone off exactly as planned. No Marine had been killed. Seventeen were wounded. With Wolmi-do neutralized, preparations for the assault on Inchon itself got underway without pause, even though the actual landing would not be possible until the evening high tide at 1730. As Taplett's Marines were rounding up the last of Wolmi-do's defenders, Navy Corsairs and Douglas Skyraiders from RADM Edward C. Ewen's Task Force 77 began interdicting everything that moved within a 25-mile radius of Inchon. At 1430 the big guns of the cruisers joined in, pasting targets in the city's eastern and northern outskirts. As the assault elements of LtCol Murray's 5th Marines and Col Fuller's Ist Marines began boarding landing craft, the destroyers opened close-in fires at the landing beaches: Red and Blue. The beaches were no prize. Red Beach, the zone of the 5th Marines, was no proper beach at all. The water ended abruptly at a stone seawall that even at high tide would require Murray's Marines to exit their landing craft by scaling ladders. The Ist Marines' Blue Beach was little better. A bit wider than Red Beach to the north, it did not exit directly into the city. Even so, Blue Beach with its constricted exits would not have been looked at twice by an amphibious planner with any choice in the matter. Unfortunately, Red and Blue were all there was. They would have to do. Sergeant Irvin R. "Dick" Stone, an assault section leader in Weapons 1/5, had gone ashore at Peleliu exactly six years to the day earlier. At Peleliu there at least had been a beach. At Inchon, as soon as he stuck his head above that seawall, he would be in the middle of a city. Stone didn't relish the prospect. At 1724, with intermittent rain squalls spitting down, Stone and the leading waves of 1/5 crossed the line of departure and headed for that ominous seawall. Preceding them was a shower of 5-inch rockets, more than 2,000 of them, fired from LSMR-403, blanketing the beach and its north flank. Almost too soon for the Marines in them, the landing craft snubbed their noses against the sheer face of the seawall, and the scaling ladders were thrown into place. Among the first over the wall was First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez, leading his 3d Plt of A/l/5. A former Navy enlisted man in World War II, Lopez had entered the Marine Corps via the United States Naval Academy, where he had been a standout boxer. Confronted immediately by a bunker, Lopez silenced it with a grenade, then turned to hurl another grenade at a second bunker. Bullets ripped into his arm and shoulder. The armed grenade dropped to the ground. Unhesitatingly, Lopez fell upon the grenade and drew it to him, absorbing the full force of the blast as the grenade detonated. His selfless action would bring him a posthumous award of the Medal of Honor. With LtCol George Newton's 115 and LtCol Hal Roise's 2/5 advancing on line, the 5th Marines overwhelmed the North Korean defenders of the 226th Regiment. Together the two battalions swarmed up the slopes of the initial objective, Cemetery Hill, and rolled toward the higher bulk of its neighbor, Observatory Hill. The North Koreans they encountered were still dazed by the pre-assault fires. Some stood and fought. They were overcome. Others were too stupefied to resist. They were herded away as prisoners. By 1815 Observatory Hill was firmly in Marine hands. Also in Marine hands was the lucrative prize of the Asahi Brewery. Covetous eyes grew glum as the brewery caught fire and burned itself to a gutted ruin to the accompaniment of exploding kegs and bottles and assorted muttered curses. While the 5th Marines were clamping a firm grip on the city, the 1 st Marines were cutting across the city's southern edge. Their mission: to secure the main approach to the city proper, opening the way for an advance upon Yongdungpo and Seoul. Like the 5th Marines, the Ist Marines landed with two battalions side by side-LtCol Allan Sutter's 2/1 on the left and LtCol Tom Ridge's 3/1 on the right. Landing from Luis (tracked landing vehicles which were forerunners of today's assault amphibious vehicles), Sutter's and Ridge's leading waves were ushered ashore by a resounding bombardment by HMS Jamaica and HMS Kenya, the destroyers USS Gurke and USS Henderson, and a deluge of rockets sent roaring over by LSMR-401 and LSMR-404. There were still North Koreans willing to fight. They were no match for Chesty Puller's Ist Marines, a crushing hail of naval gunfire and the bombs, rockets, napalm and 20 mm gunfire of Marine Corsairs and Navy Skyraiders. As if to underscore the effect of all this ordnance, fires from HMS Jamaica set off a North Korean ammunition dump with a stupendous roar. Ashore, Sutter's assault companies, Dog and Fox, landed against light, scattered resistance. In pitch darkness and constant rain the Ist Marines' fire teams slipped, stumbled and cursed their way to their initial objectives, routing the few dazed defenders who attempted to oppose them. By 0200 on the morning of 16 Sept., Inchon was firmly in Marine hands. A 1stMarDiv that had been cobbled together from nothing had streamrolled everything in its path. Total casualties amounted to 21 Marines killed, one missing and 174 wounded. It had been a textbook Navy-Marine operation, one that had taken the North Koreans completely by surprise. Despite the staggering natural obstacles, by the end of D-day RADM Doyle had put 13,000 troops ashore. Speaking of the commander who had refused to accept the impossibility of Inchon, LtGen Shepherd, a future Commandant of the Marine Corps, said, "Doyle is a great commander and is the best naval amphibious officer I have ever met." It remained for Gen Oliver P. Smith to have the final word, "The reason Inchon looked simple was that professionals did it." |

||||

|

||||

|